I thought I’d wrap up my recent mini-series about Robert E. Howard’s recurring sword & sorcery heroes by discussing the least renowned of the bunch, Bran Mak Morn. Like Conan & Kull, Bran Mak Morn is a barbarian king. But unlike these other two, Bran is not the usurping king of the most civilized nation in the world. Instead, he is the king of his own people, the savage remnants of the once proud Picts.

Like Howard’s other sword & sorcery heroes, Bran Mak Morn made his first appearance the magazine Weird Tales, in the November 1930 issue, with the story “Kings of the Night.” As it happens, this tale also features an appearance by King Kull, and would mark the sole crossover tale among any of Howard’s primary S&S heroes. In total, Bran Mak Morn would appear in two stories during Howard’s lifetime. If you include “The Dark Man” and “The Children of the Night”—a pair posthumous tales either about or concerning Bran Mak Morn some years after Bran’s death—that brings the total to four. If you’ve read my other articles on Howard’s creations, it should come as no surprise that in the decades following Howard’s suicide, a host of unpublished materials about Bran found their way into print.

In addition to discussing Bran Mak Morn, I should also note that Robert E. Howard had a lifelong fascination with the Picts. His first Pictish tale appeared in (you guessed it) the magazine Weird Tales, in the December 1927 issue, with the story “The Lost Race.” But Howard didn’t stop there. In his Kull stories, Kull’s closest friend and adviser was Brule the Spear-Slayer from the Pictish Isles. In this time line, the Picts haven’t fallen into savagery yet. This isn’t the case with his Conan stories. Here, in the times following the Cataclysm that rocked Kull’s world, the Picts have degenerated into a primitive people, as shown in what I consider one of Howard’s stronger Conan tales, “Beyond the Black River.” These Picts are closer to what we witness in the Bran Mak Morn stories, the remnants of a savage people on the verge of being wiped out by the conquering Romans and neighboring Celts. Besides “The Lost Race,” Howard also wrote a number of Pictish tales having nothing to do with these heroes, including the classic must-read, “The Valley of the Worm.”

To an extent, the creation of the Bran Mak Morn represents the culmination of Howard’s fascination with the Pictish people. This character is the last hope of his doomed people. However, other than ties of blood, Bran Mak Morn is very little like them. He is taller, stronger, and smarter. He even looks less primitive. He comes from an unbroken bloodline, the old Pict more in keeping with Brule the Spear-Slayer than the Picts of Conan’s Hyborian Age (and we actually learn in “The Dark Man” that Bran is descended from Brule’s line). He is not just struggling to save his people from the Romans and Celts (with some magical situations mixed in, of course), but also to restore them to their lost glory.

Nearly all of Howard’s supernatural tales contain a dark grittiness and the Bran Mak Morn stories are no exception. That said, I believe the particular blend of dark grittiness Howard relies upon with these stories are a big reason why of all his major recurring sword & sorcery heroes, Bran Mak Morn always seems to be the one that is discussed the least. There is a depressing inevitability that pervades Bran’s tales, a sort of literary malaise that makes it difficult to get as excited about these stories as those of the other heroes. Conan was a man who lived in the moment, from adventure to adventure. Kull sought answers to the great mysteries of life. We never learn if Kull achieves those answers, but in the Kull stories it is the search that matters most. With Solomon Kane, he is doing exactly what he wishes, battling evil in what he believes is God’s name.

Bran’s situation is different. He is the last of his noble line. He is a hero born in the wrong time, a man championing a doomed cause. He can win the battle, but the war is a lost cause. He can save today, but tomorrow offers little hope. Eventually the last remnants of his people will fade from the Earth, and despite his heroic efforts, there is nothing he can do to stop this. He can put it off (and does, as we see short term in tales such as “Kings of the Night” and longer term in “The Dark Man”) but the final conclusion is foregone. His goals are beyond his reach. Still, he fights, he fights well, and he refuses to give in. And that’s why we root for him and why he’s worth reading about.

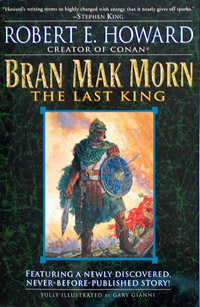

If you’re curious about the stories of Bran Mak Morn, Del Rey has put together a collection called Bran Mak Morn: the Last King. It compiles all of Howard’s writings about the Pictish king, and is part of the same series of books I’ve mentioned in previous entries. Bran may not be as renowned as Howard’s other heroes, but his stories are no less primal and evocative. Kull fans will certainly want to read “Kings of the Night” and many Howard aficionados consider “Worms of the Earth” to be one of his finer works. You could do worse than to pick up this volume.